To celebrate International Women’s Day this year, thousands of women took to the streets in major urban centers including Toronto and Vancouver demanding gender equality and proclaiming women’s rights.

These marches called to global attention the fact that there’s still a lot to be done to advance women’s rights all over the world including Canada where undervalued women do housework and provide child and elderly care every day in every Canadian home.

Female Family Members as Caregivers

- In general, female family members – from wives, mothers, grandmothers to aunts, nieces, sisters – do a lot more housework and care for the young and old than any male member of the family. (Watch for our Editorial on this topic in May 2020.)

- These home builders and caregivers do all they can – both inside and outside the home – for the good of the family. Their work is endless, their sacrifices innumerable, their patience immeasurable, their love unconditional and endless. Their reward: love and affection, honor, respect and pride in the family’s achievements.

Foreign Domestic Workers and Caregivers in Canadian Life

- Foreign caregivers and domestic workers have been coming to Canada for over a hundred years. In the 1800s, European women came to be household helpers. There were no restrictions on their becoming permanent residents or citizens in Canada. In fact, they were invited to immigrate and become full pledge Canadians.

- The last half century has seen the change of source countries for this vital labour force. Canada’s Foreign Domestic Movement (FDM) established in 1981, targeted Caribbean women primarily and its successor, the Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP), started in 1992, attracted Asian women. Both groups are women of color and are not given as easy access to permanent residency and citizenship as those European women before them who came to do the same work.

A. Current demographic characteristics

An updated study of caregivers and domestic workers in Canada shows their current characteristics:

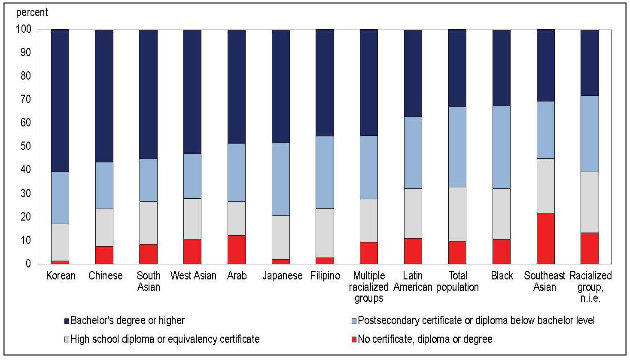

- The educational level of LCP principal applicants has increased steadily over the years, and is now very high.

a. In 2009, 63 percent of applicants held a bachelor’s degree or higher. This is a remarkably high proportion, and far exceeds the proportion of principal applicants in ‘economic’ categories of immigration who have university degrees (39.5percent).[CIC Facts and Figures, 2009: p42].

b. From 1993 to 2009, 444 principal applicants had Masters degrees and 48 had earned doctorates. - The majority of principal applicants are aged between20-40.

- Principal applicants are more likely to be married.

- The overwhelming majority are women.

- Over 90 percent have come from the Philippines and are proficient in English.

B. From the lens of the Federal Skilled Worker Program.

If the LCP applicants were evaluated under Canada’s Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS) or Points system based on skills, education, language ability, work experience and other factors such as age, most would easily score 67 points or higher out of 100 to qualify to immigrate in Canada under the Federal Skilled Worker Program.

C. Needs and Socio-Economic Implications of Canada’s Ageing Society

- With low fertility rates and more Canadian couples getting married at a later age, the number of those who are 65 years or older are expected to double in less than two decades from 5.0 million to 10.4 million in 2036.

a. In 2014, over 6 million Canadians were aged 65 or older, representing 15.6 percent of Canada's population.

b. By 2015, 1 in 4 Canadians were 65 years and older. For the first time, there were more Canadians over the age of 65 than under the age of 15.

c. By 2030 - in just 10 years from today - seniors will number over 9.5 million, making up 23 percent of Canadians.

- The greying of Canada’s population carries the following socio-economic implications:

a. increasing need for caregivers;

b. less revenue for government; and

c. rising healthcare costs.

A 2002 study conducted by Health Canada found that 44% of family caregivers paid out-of-pocket expenses; 40 percent spent $100 to $300 per month on caregiving, and another 25 percent spent in excess of $300.

- The costs of caring for ageing parents:

- The cost of elderly care amount to $33 billion a year in out-of-pocket expenses and time is taken from work, and are expected to grow (according to a report by CIBC economists);

- average $11,635for those 65 and increase to as much as $21,150 for those 80 and older. (according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI);

- In Canada, the government only pays 70 percent of healthcare costs. The other 30 percent is left for seniors or their family members to pay.

- After the age of 65, Canadians expect to spend an average of $5,391 every year on out-of-pocket medical expenses. Family caregivers spend an average of $3,300 a year on these expenses.

- Family members who cared for ailing children or older relatives reported more health and psychological problems, mainly because of the intensity of care provided. Those who cared for an ailing spouse also experienced financial difficulties as a result of their caregiving responsibilities and loss of spousal income.

- Without caregivers employed by families to look after their ailing spouse or parents and grandparents, the government will have to spend billions of dollars to provide institutional care where needed. Even at that, most nursing homes have been found by families to be wanting. }

D. Consensus

- The best place for ailing old people is at home in the compassionate care of competent caregivers privately paid for and supervised by family members.

- This is how the government can ensure the proper care of Canadian seniors and at the same time save money in institutional care and health care costs.

- Also, this approach would generate more revenue for the government because more women will be able to work outside the home.

- The services provided by foreign domestic caregivers and workers are essential and the need for them will be heightened with the rapidly increasing number of ageing Canadians.

- The Philippines has been the dominant source of foreign domestic workers and caregivers (not only for Canada but also for the US, Spain Israel, etc.) because Filipino caregivers are well educated, have facility with one of Canada’s official languages (English), share similar cultural and religious values, committed to hard work and industry, and imbued with a deep sense of caring for others.

- Indeed, foreign domestic caregivers and workers, most of whom are women, are able and available to meet Canada’s labour force needs, now and in the future.

E. Conclusion

Although the LCP was discontinued in 2014, there are about 24,000 caregivers and their family members who came under this program and who are still struggling to get permanent residency, reunite the family and secure a decent future in Canada. Due to certain restrictions of the LCP, years of family separation have caused familial conflicts between alienated caregiver-mothers and their estranged children resulting in many family breakdowns and marriage failures.

These caregivers and their family members have suffered long enough. The current immigration pilot projects are mere bandaid-type solutions to LCP-caused problems and only prolong their uncertainty and insecurity. It is time for this social injustice to end. These care workers should be allowed to become permanent residents without making them jump through hoops. This is the only just solution to this social injustice – landed status now.

Because they are qualified as skilled workers, future caregiver applicants should be admitted as regular immigrants with permanent resident status on arrival and with the same right as other immigrants to seek a better life and a brighter future for their children in Canada. Because they provide an essential service to Canadian families where both parents work and to the increasing number of ageing Canadians in need of competent, compassionate and relatively affordable and flexible care, the processing of caregivers applications as regular landed immigrants should be expedited so that they arrive in Canada within two years upon application. These caregivers come from poor developing countries and do not have the luxury of time. They cannot afford to wait three to five years before landing a job when their work is in demand in Canada. Giving them the opportunity to improve their future would truly advance all women’s rights in Canada and show appreciation of their work and contribution to Canada’ development and progress.