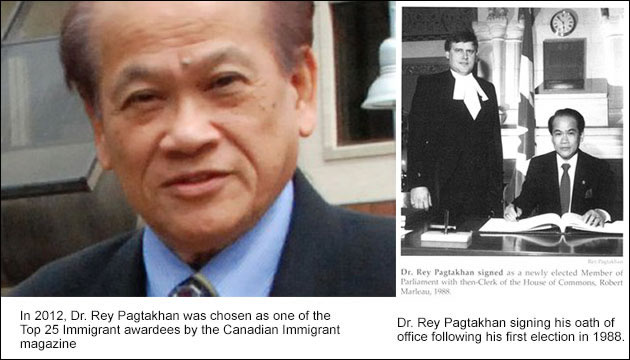

Dr. Rey D. Pagtakhan, a lifetime member of the Privy Council for Canada and listed in Canadian Who’s Who, is a community volunteer and pediatrician-turned-politician.

Now retired from both careers, but not from his community advocacy, he became the first ever Canadian Filipino elected to the highest elective body in Canada – the House of Commons.

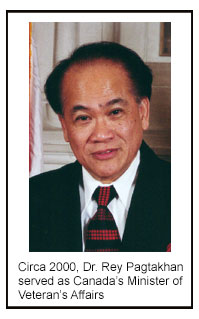

During his decade-and-a-half political tenure, Pagtakhan served as vice-chair of the Standing Committee on Health, Seniors, and the Status of Women and as Critic for Health in the shadow cabinet of the Official Opposition. While in Government Caucus, he served as chair of the Standing Committees on Citizenship and Immigration and on Human Rights and as Parliamentary Secretary to the Prime Minister. Later, he was cabinet minister for Asia Pacific, for Science, Research and Development, for Veterans Affairs, and for Western Economic Diversification. Additionally, he served as senior regional federal minister for Manitoba.

Pagtakhan takes just pride in what he set out to accomplish, more particularly in bringing back to Winnipeg and to Edmonton two Filipina deportees and preventing the deportation of half a dozen more. Through this interview, the Canadian Filipino Net distills some pointers from his remarkable Canadian political journey and now shares these with our readers starting with this issue.

Eleanor Guerrero-Campbell: You were a physician at the time you entered politics. What made you go into politics?

Rey D. Pagtakhan: What made me go into politics was my wish to contribute the best in me – my skills and collective life experience – to decision-making at the national level and thereby make a positive difference in the lives of many more people. By bringing my insights to Parliament and the Government of Canada, I thought that I would serve a greater number of citizens from all walks of life, here and even abroad. My public contribution and service would then extend beyond the clinical boundaries of diagnosis and treatment of illness in an individual patient to development of governmental policies and programs to help address the illnesses of society and to help advance the prosperity of our adopted country. In essence, to give back to the community for the many blessings Canada has showered us and for the beneficence I had been fortunate to receive during my growing up years.

EGC: Were you hesitant at all?

RDP: Yes, I hesitated and agonized long and hard because of the twin images of politics. I had known about the unpredictability of political life and the risks that it poses to aspiring politicians and their families. I was a witness to a family friend’s near calamitous divorce. I intervened and provided counselling. I had heard of individual’s reputation tarnished and life self-destroyed as a consequence. I had heard stories of friendships broken and community camaraderie strained.

And I had been keenly aware of the public perception that holds physicians very high in the pedestal of public esteem than politicians who are deemed only above murderers and thieves.

That is the ugly image. I even worried about what my colleagues at the university and hospital might negatively say. Even our oldest son, Reis, then a 17-year old teenager and still at university (now a lawyer), found it initially difficult to understand my dilemma. “You are crazy, Dad,” he remarked one night at the dinner table as I announced my imminent decision, “why are you leaving a high-paying for a low-paying job?” “You are correct, son,” I simply answered, “If it were simply like any other job.” And I quickly added: “Politics, like medicine, is a noble calling.”

That is the beautiful image. Whether we like it or not, politics has an overwhelming influence on the lives of a nation’s people and her institutions, on the civic and educational aspirations of our youth, on the plight of the vulnerable and marginalized sectors of our rank and file, on the security and safety of our seniors, on the stability and strength of our social programs, on the integrity and independence of our judiciary and civil service, and on the prosperity, vitality and very essence of nationhood itself.

EGC: Did your childhood and growing up years influence your decision? How?

RDP: I remembered how my parents endeavored to send me to medical school and how the community helped along the way. I remembered the help of college teachers (Professors C. Mojica and V. del Fierro) who offered me free board and lodging while I was in pre-med at the University of the Philippines Diliman campus, the home of my classmate (Dr. A. Alday) that became my free dormitory while I was in the medical school proper in Manila, and the plane fare in cash from my pediatric professor (Dr. L. Mabilangan) so that I could go directly to the St. Louis Children’s Hospital of Washington University School of Medicine in Missouri, USA without worrying about a ‘fly-now-pay-later plan” from a travel agency.

I remembered, too, the joy of my doing general practice (GP) in Bacoor, Cavite – the town where I grew up – without my patients ever to fear about medical fees. And I would always remember the teaching of my mother never to forget to give back at the first opportunity. Politics is that window of opportunity.

EGC: What were the turning points and issues that led you to your political career?

RDP: The possibility of politics being my second career entered my consciousness in the summer of 1982. I was then in Tucson, joined by my whole family – my wife, Gloria, and four sons, none of whom had become a teenager – spending a year (until June 30, 1983) of my sabbatical leave at the University of Arizona Medical Center. The political seed, if I may, was planted in me after reading the inspiring autobiographies of Abba Eban (former Israel’s Ambassador to the United States and Delegate to the United Nations) and Anwar Sadat (former President of Egypt who brought peace between his country and Israel).

I was elected President of the United Council of Filipino Associations in Canada in 1982. Upon my return to Winnipeg that following June 1983, a racial discrimination issue involving the Winnipeg Police Force and the Filipino community had occurred. I led the delegation that appeared before the former Winnipeg Police Commission only to be told the issue was not within its jurisdiction. Disappointed, I asked for all the documents related to the Commission. Soon, the Mayor of Winnipeg Bill Norrie – a Rhodes Scholar during his youth – invited me to serve on the Commission, the Winnipeg Police Department’s civilian oversight body. I served until 1986, the year I was elected to the St. Vital School Board.

In 1986, I joined the 27-member official delegation of CIDA’s (Canadian International Development Agency) Program Planning Mission to the Philippines soon after former President Cory Aquino was installed into office following the People Revolution. I formed part of this delegation on behalf of the Filipino community nationwide, upon the invitation of the Foreign Affairs Minister Joe Clark for the Government of Canada.

The year before had seen me elected as Chair of the Board of Presidents of the Canadian Ethnocultural Council (a coalition of 37 national ethnocultural organizations in the country – Arab, Chinese, German, Japanese, Jewish, Latin Americans, Polish, Sikh, Ukrainian, Vietnamese, etc.) and its Executive Vice-President.

I must say that my extracurricular activities had given me first-hand knowledge and a better appreciation of the varied and broader community issues – racial discrimination, recognition of foreign-obtained credentials, foreign aid budget, under-representation of visible minorities in government boards and agencies, unjustified decisions by quasi-judicial tribunals involving newly arrived Filipino immigrants, Japanese redress issue and issues of other ethnocultural groups, threats to Medicare, the prevalence of poverty, to mention a few – and how solutions were searched and found.

I joined the Liberal Party of Canada in the spring of 1985. I got elected to its Provincial Executive and chaired a political policy workshop for the first time. As Co-Chair of the fundraising dinner the following year, I had the privilege of introducing the Right Honourable John Turner – our Keynote Speaker. He strengthened my belief about the nobility of politics. Thus, my continuing attraction to consider politics as the next natural step in my personal search for a deeper purpose in life continued to make traction.

EGC: When you were beginning to engage politically, you were still a physician. How did you juggle these two demanding activities?

RDP: Attending to my patients and their families, teaching students who want to become doctors and young doctors to become lung specialists, and doing medical research to add to the body of medical knowledge – all these had been a passion that I pursued with dutiful attention.

Just as my community engagement was in full swing, I was at the same time giving more lectures at national and international medical conferences and contributing more papers and chapters to medical journals and books. And it was around this time, too - 1985 - that I received my promotion to full Professor of Pediatrics and Child Health at the University of Manitoba Faculty of Medicine. This could not have come at a more appropriate time. I was 50 and ahead of me were some 15 years and then Professor Emeritus, perhaps.

“To be a politician or not to be?” kept visiting my thoughts at increasing frequency. Indeed, deciding to make the initial change from medicine to politics was truly the most difficult aspect of my political journey.