The elimination of poverty is one of the loftiest goals of government.

However, delivering on this objective is easier said than done.

One of the many ideas that have been around in various parts of the world with respect to poverty eradication is a universal basic income.

With this measure, everyone is guaranteed by the government a minimum income that is enough to cover the cost of living, no strings attached.

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to this policy. There’s a one-size-fits-all model, where everyone receives a cheque. The other is a negative income tax approach, where the richest get nothing, and the poorest, an income supplement.

In Canada, the concept of a basic income was tested during the 1970s in the small city of Dauphin in Manitoba, which was the first of its kind in North America.

For five years, monthly cheques were provided to the poorest residents to top up their incomes.

Political changes on the provincial and federal level led to the cancellation of the experiment.

As one might expect, basic income is a contentious topic.

Proponents argue that governments, in one way or another, already spend tons of money in dealing with the effects of poverty, so why not break that cycle altogether?

In Canada, there are various social assistance programs on the federal and provincial levels. The Canada Child Benefit for poor families, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement for low-income seniors, are two examples.

In addition, governments also cover costs for healthcare, policing, and courts to address the social ills often associated with poverty, like crime.

Opponents of basic income argue that this measure will serve as a disincentive for people to work.

They also point to the challenge of how minimum levels of income should be set to truly guarantee that people will be lifted out of poverty.

Moreover, opponents say that this approach will be an added burden to taxpayers.

In April this year, the Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) released a costing of a national guaranteed basic income.

According to the estimate, the gross cost ranges from $76 billion to $79.5 billion for the period 2018-2023.

The PBO, which provides independent budget analysis to the Senate and House of Commons, forecast that more than 7.5 million people would benefit from the basic cost of a guaranteed basic income.

The office also noted that the federal government currently spends around $32 billion to support low-income Canadians. If the amount was deducted from the low estimate of $76 billion, the net cost for the national government would be $44 billion.

As well, this cost can be lowered if provincial expenditures to support poor families and individuals were to be subtracted.

In Ontario, the government of then Liberal Premier Kathleen Wynne started to implement a pilot project on basic income in select areas of the province in 2018.

Some 4,000 participants were chosen for the three-year trial. They are people living on incomes under $34,000 per year for a single person, and less than $48,000 per year for a couple.

Under the pilot, a single person will receive a guaranteed sum of $16,989 per year, less 50 percent of any earned income. For couples, it’s $24,027 per year, less 50 percent of any earned income.

The pilot didn’t get too far. In June 2018, Doug Ford and Progressive Conservative Party were elected to office. In July this year, the Ford government announced that it is cancelling the experiment effective March 2019.

In the west, British Columbia could have its own test.

Last summer, the B.C. NDP government announced the formation of an experts’ panel to explore how basic income can be explored in the province.

The move was in connection with the B.C. NDP and B.C. Greens’ agreement in 2017 to form a government.

The so-called Confidence and Supply Agreement between the two parties included an understanding to “design and implement a basic income pilot to test whether giving people a basic income is an effective way to reduce poverty, improve housing, health and employment”.

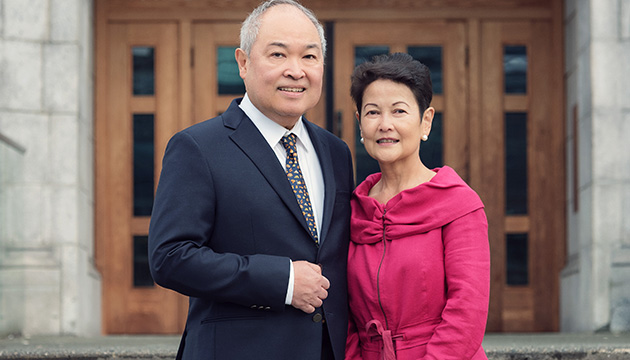

The panel chaired by David Green, director of UBC’s Vancouver School of Economics, will look at research and see how a pilot program can be implemented.

By the CFNet Editorial Board

Contact us at: